|

|||||||||||||

|

New Book |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

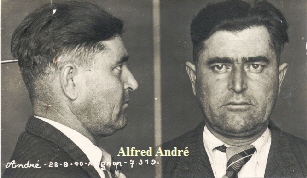

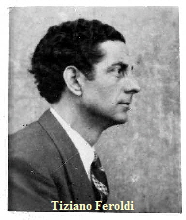

Alfred André and his Victims Alfred André was 47 at One of his brave deeds was the arrest of the Jews in Bollène in March 1944. He admitted to his participation in the raid during his interrogation of June 15, 1945: While I was at the offices of the Geheime Feldpolizei in Avignon, The young milicien who accompanied Feroldi gave us directions, but he did not accompany us. We arrived in front of a castle which I knew later belonged to an Israelite named Rosenberg. Feroldi entered the yard through the large gate. We heard people running and the lights went off in the castle. Shots were fired by the Germans accompanying us. Feroldi and I, entered the corridor and we were rejoined by two miliciens and a German flanking the owner of the castle, M. Rosenberg and three daughters. All had been arrested in the park. I stayed in the living room to guard the four people. Meanwhile, the others went to the castle wing inhabited by the farmer and arrested the German deserter we were seeking. Two Alsatians were also arrested, but outside the castle. On the following day trucks arrived. The seven people arrested sat in one of them. The furniture, paintings, etc. were looted in this castle. In the course of this operation, the miliciens looted all the rooms. One part was kept by Feroldi, rue des Lices, Caserne des Passagers; the rest at the headquarters of the Milice, rue Joseph Vernet. The Germans took away all the wine: 250 liters. Personally, I did not participate in the plunder because I was guarding the defendants [sic]. I swear to you that I did not receive from the Milice anything from this pillage. The manhunters were seeking a deserter from the German army and ran into the Rosenberg family. André’s deposition clearly indicates that, in addition to the Rosenbergs, the Nazis had found the deserter in question and several other persons of interest. Of course, it is possible that they found the Rosenberg family by accident because the deserter was hidden in their farm. But it may also be possible that, from the time of their departure from Avignon, they had in fact intended to arrest the Rosenbergs. In this affair, André accused Feroldi, a milicien who was largely in the same class, but no longer available to account for his deeds, since he escaped justice. Today, the veil over the circumstances of the arrest of Szlama Rosenberg, his daughter Marceline, and two refugees, Marie and Suzanne Melman, who were also unfortunately Jewish, is lifted. All were deported on convoy 71. On that day, the entire family would have been arrested, but Jacqueline Rosenberg, now Mme. Haby, and her little brother Michel, who had been hidden by their parents at a woman’s home in Bollène, were saved. It is a miracle that the mother and Henriette, the eldest daughter, were able to escape by hiding in the garden. The Melman sisters who happened to be present at the wrong time were captured with Szlama Rosenberg and his daughter Marceline. In 2008, in her autobiography, Ma Vie Balagan, Marceline, an Auschwitz survivor, recounts the circumstances of her arrest. With some minor exceptions, her story sadly echoes Alfred André’s confession. On the morning of February 28, 1944, my eldest sister, Henriette, who belonged to the Resistance, came to warn us not to sleep in the château that night. So, during the day, my father had carried some of our belongings up the mountain, to an abandoned house, full of bugs… At home, that night, there were two girls, two sisters, Marie and Suzanne [Melman]. Since they had not found a place where to flee, my parents had offered them to hide with us in that abandoned house, in the forest. It was in winter. It was very cold. My mother had cooked a pot-au-feu. She said: “We are not going to leave tonight, I have a terrible headache”… The memory of that day has not faded away: I remember it’s getting darker. I remember the last pot-au-feu prepared by my mother. I remember our fatigue, the migraine of my mother, and the insistence of my sister [Henriette] pushing us to leave. I remember the decision to stay… one more night. I remember, I am the first to go to bed on the second floor, and I fall asleep. I am 15 years old. I remember: I am suddenly awakened by my father “Fast, fast, Marceline, they are here”… I remember, completely in the dark, the yells “Open, open”, the screams, the gate of the internal yard being opened by M Roussier, our tenant farmer, who lives right behind. I remember the violent knocks on the doors, the submachine gun shots, and of my frantic flight amid yells, screams, “Open, open, you are finished”. I remember running from one stairwell to another; I remember that I do not succeed in coming downstairs, as the shots become so much precise. I am alone in the house. I must get out at all and reach a hidden door, at the end of the park, leading to the woods. I remember: with fear in my stomach, I succeed in leaving the house. My father, mad with worry, is waiting for me behind a tree, at the beginning of the park. I remember I saw only him; we run like mad towards the edge of the park, in the darkness. I remember, I am ahead of him, I unbolt the door, I say “That’s it, Daddy, we are safe”. Behind the door, a man, a French milicien, revolver in hand, a flashlight in the other hand. He tells us “Halt, or I shoot!” He violently hits my father on the head with the butt of his gun. I remember our return to the dining room; the pot-au-feu is still on a corner of the wood stove. It is midnight, they are a dozen, French miliciens from Bollène, from Avignon, Germans in uniform, from the Gestapo, dressed in black, all armed. I remember their violence, the brutality of the interrogations. I remember the looting of the château, the truck arriving, the furniture they are moving, the despondency of my father who is suffering from the blows he has received and the slaps that come my way, the milicien who wants to rape me. I remember my cries. I remember this German officer, rushing in and screaming: “It is forbidden to touch this dirty race”. I remember this dreadful phrase that saved me. I remember the evasive look of M. and Mme Roussier who witnessed it all. I remember the next day at noon, the departure on the trucks, crammed and sitting on chairs from the château… From the château, the prisoners are taken to the Ste Anne Prison, from there to the Grandes Baumettes in Marseille, then to Drancy. Marceline had noticed an unusual German officer: There was a German, a very classy one. He told me “I am a member of the Fifth Column. The Fifth Column was an intelligence organisation already present in France before the war. I was a German teacher at the lycée Lakanal, in Sceaux.” This man probably is Wilhelm Wolfram, aka Gauthier, a subordinate of Wilhelm Müller, the head of the Avignon German police. The testimonies lead to the first question “Who knew of the existence of the Rosenbergs?” Of course, the farmhand and his family were aware, but they were not the only ones. Moreover, we know from several sources that the Rosenbergs were well known in Bollène; well-off families indeed do not go unnoticed in small towns. They had been registered in the census of 1941, 1943 and 1944; their names had been collected by the Bollène town hall and the prefecture of Vaucluse. We also know that the list of foreign Jews they were a part of had been communicated to the Germans in October 1943. Moreover, we also know that, on January 28, 1943, Georges Cruon, a violent and greedy anti-Semite, forwarded to de Camaret the list of 38 Jews of Bollène, amongst them the Rosenbergs. Self-appointed as the chief supervisor of the Bollène Jews, Cruon surely gave away this information to whoever asked for it. Finally, on December 7, 1943, the SEC of Marseille transmitted to Jean Lebon “… for execution… letter No 38200 from the CGQJ relative to the Bollène Château du Gourdon affair (the Jew Rosenberg)”. Apparently, like many other Jews, the Rosenbergs lived out in the open. The second question is: “When did the members of the GFP learn of the existence of the Rosenbergs?” According to the deposition of Alfred André, the raid on Bollène was first and foremost motivated by the arrest of the German deserter whose hiding place was known to the GFP. Besides, a police report relates that, on March 3, 1944, “… at M. Jean Roussier’s home, [the German police seizes] a radio set, linen and money in the amount of 20,000F…” It is thus possible that the German police had become aware of the Rosenbergs on their arrival at the home of the farmhand, whom they roughed up, but it is equally possible they had known all along who were the owners of the Château and the farm. There is no obvious way of determining the scenario that led to the Rosenbergs’ arrest. Another aspect to this case, hidden by Alfred André, was disclosed by his friend Jean Costa, who became acquainted with André at the penitentiary in Nîmes (they had shared a similar prison experience). They reconnected at the Hotel “La Cigale” where Costa was interrogated by the Germans for arms trafficking, before he was hired by them at the GFP. Costa shed light on the raid in Bollène during his deposition on June 28, 1945. I did learn that André had participated with the Germans in the arrest of the three Israelite girls. Later, the mother who had fled through the garden was put in contact with André, without the knowledge of the Germans, through the intermediary of the owner of the Crillon, Paul Biancone. André wanted 500,000 francs to get her three daughters out. This woman transferred the amount in question, but her children were nevertheless deported. Jacqueline Haby testified that in fact her mother had to pay double the amount cited by Costa. One way or another, the money at stake was considerable, and one can easily imagine how the money was split among all the intermediaries. Biancone ran the bar “Le Crillon”, one of the meeting places most prized by the hooligans of the Vaucluse collaboration. Alfred André did not stop at the arrest of Szlama, Marceline and the Melman sisters; he jumped at the opportunity to demand a ransom from the family. Mme Frenata Rosenberg did not disappoint him in her desperate hope to snatch her husband and the three girls from the clutches of the criminals. Marceline continues: I remember the arrival at the Auschwitz train station, the opening of the cattle cars, the screams, the SS, and a few rare French words, meant to be reassuring, which we could not grasp: “Give the children to the elderly, do not get up on the trucks…” I remember the hunger which gnawed at us day and night, the blows, all the humiliations, the cold, the roll calls, the selections for the crematorium, our cheeks which we were pinching to look well before walking in front of Mengele, the camp doctor in chief, the wounds which we attempted to hide to survive, the kapos, the roads we were paving, our skinniness, my father whom I saw by chance, who held me tight against his chest. I remember the SS who beats me to death in front of him while he called me a whore, and I fainted. I remember being happy that my father was alive. I remember: Birkenau, Bergen-Belsen, the death of Simone Ragun’s mother, Theresienstadt, Prague, the return, the Hotel Lutétia in Paris. My father will not come back. I would learn later about his long forced march from Auchwitz to Gross Rosen in Germany, the liquidation of all the survivors by the SS, the Russians arriving and finding only corpses… An Auschwitz survivor, later married to Joris Ivens, the famous documentary maker with whom she created a large cinematographic body of work, Marceline Loridan Ivens produced in 2003 “The Little Meadow with the Birch Trees”, a film with Anouk Aimée inspired by her own deportation. |

|

|

|

|

Francais |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

the time of his arrest; he was a native of Aigues-Mortes and resided at 30, rue du Rempart St Lazare in Avignon. Officially a stallholder – a strategic profession to catch Jews – he had, upon the arrival of the German police until his flight to Germany in August 1944, played a key role in the arrest of Jews, who were often his competitors on the open air market. Although he did not leave a systematic report, and all the circumstances are not known, what we learn indirectly from other files suggests that he was very busy and had very little time left to lay out his merchandise on the market.

the time of his arrest; he was a native of Aigues-Mortes and resided at 30, rue du Rempart St Lazare in Avignon. Officially a stallholder – a strategic profession to catch Jews – he had, upon the arrival of the German police until his flight to Germany in August 1944, played a key role in the arrest of Jews, who were often his competitors on the open air market. Although he did not leave a systematic report, and all the circumstances are not known, what we learn indirectly from other files suggests that he was very busy and had very little time left to lay out his merchandise on the market. a man named Titien Feroldi, département inspector of the Milice, came and stated that he knew the hiding place of a German deserter, hidden near Bollène. With Feroldi, there was another milicien, around 27 year old, blond, domiciled in Bollène who had provided information about the case. I do not know his name. The Germans asked me to accompany them to conduct the arrest. We left with two cars. In the first, was Feroldi, two miliciens and one German; in the second, myself, a sergeant, and two German soldiers.

a man named Titien Feroldi, département inspector of the Milice, came and stated that he knew the hiding place of a German deserter, hidden near Bollène. With Feroldi, there was another milicien, around 27 year old, blond, domiciled in Bollène who had provided information about the case. I do not know his name. The Germans asked me to accompany them to conduct the arrest. We left with two cars. In the first, was Feroldi, two miliciens and one German; in the second, myself, a sergeant, and two German soldiers.